With its 34 turbines perched on a hill in southwestern India, the Tuppadahalli wind farm generates green energy—and profits.

The wind farm and three others in India are owned by Acciona SA, an €8.1 billion Spanish infrastructure conglomerate which held an IPO of its renewables business last year. Tuppadahalli is performing so well that an Indian credit-ratings firm upgraded it, citing its strong cash position, modest debt and long-term contracts to sell the energy.

Under the standards set by a 21-year-old United Nations program, however, Tuppadahalli is considered a toddling startup that still needs regular infusions of cash to stay in business. This means it can benefit from a large and growing global market in so-called voluntary carbon credits set up to allow corporations to offset their own greenhouse-gas emissions by funding mitigation projects in other parts of the world.

Last year, Delta Air Lines Inc. bought nearly 300,000 credits from Tuppadahalli for an undisclosed price, representing about 300,000 metric tons of carbon output that would have been added to India’s air pollution had the wind farm’s energy production come instead from traditional power generation. This allowed Delta to get closer to its pledge to curb its own emissions without taking drastic actions to overhaul its existing operations, such as switching away from jet fuel or grounding planes.

Transactions like this undercut the basic concept behind carbon offsets—that they should fund green projects that wouldn’t be possible without the additional cash they bring. Now that renewable energy can stand on its own financially, some investors, researchers and government regulators say companies buying these credits are just transferring cash to other established companies. They say the old U.N. program, which spawned thousands of similar projects and makes up a large chunk of the market for offsets, is draining money from newer initiatives that need it more, such as experiments in capturing carbon directly from the air.

The end result is that companies looking to offset their emissions are buying credits in vast numbers that do little to help neutralize their carbon output.

Pedro Martins Barata, a former executive board member of the U.N. program, known as the Clean Development Mechanism, or CDM, says he is concerned the market lacks transparency, making it difficult for buyers to understand which projects would have happened without issuing credits. “No one should buy any of that stuff anymore,” said Mr. Martins, who is now a senior director at the Environmental Defense Fund, a nonprofit advocacy group.

Delta declined to comment. A spokeswoman for Acciona’s renewables unit said the company followed the U.N.’s own guidelines, and that “the U.N.’s goal is to make these investments attractive to promote clean development.”

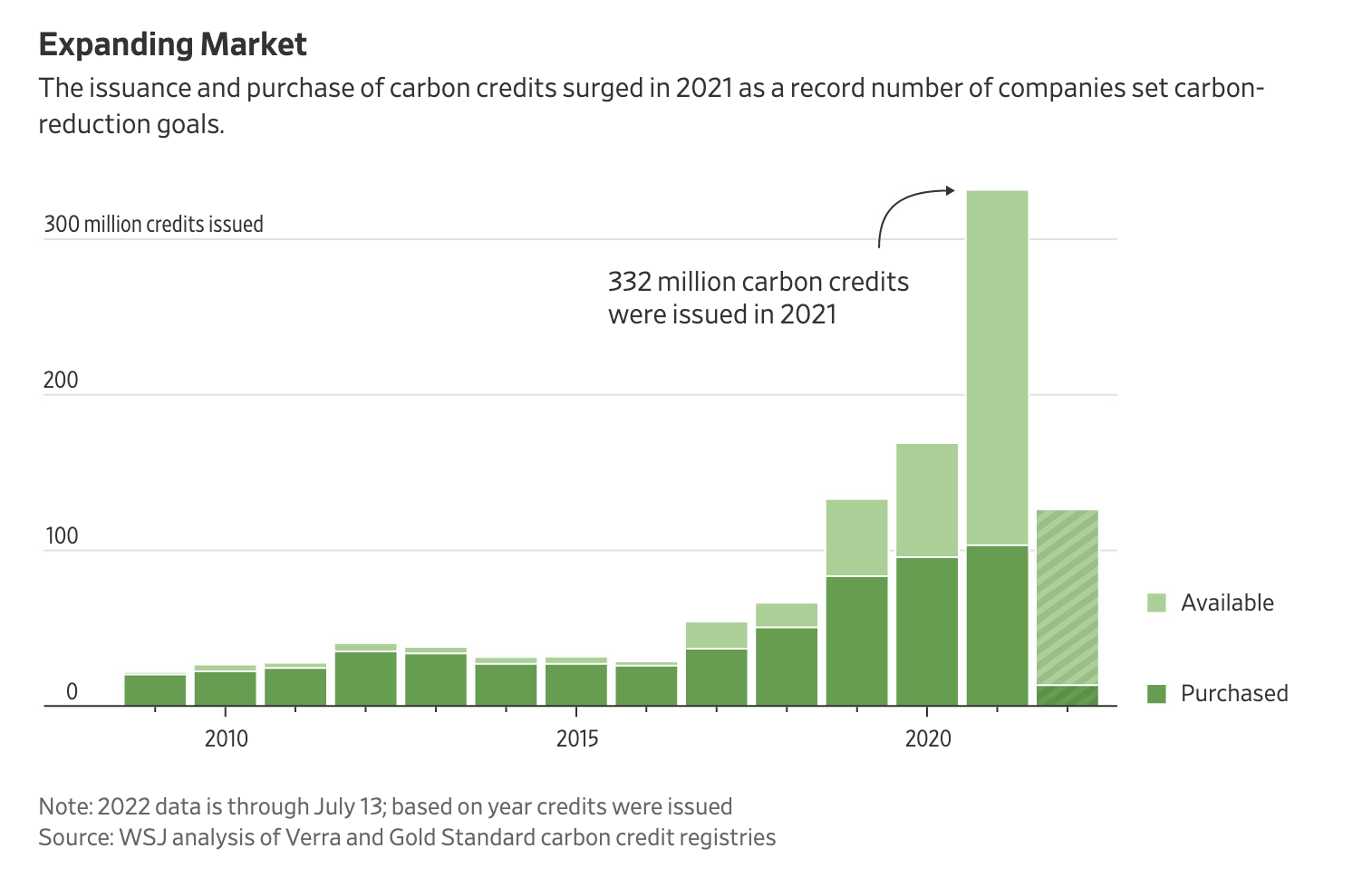

Surging demand for credits is being driven by companies, often under pressure from investors, governments and customers, to reduce their net carbon footprint. More than 5,000 companies have signed a U.N. pledge to eliminate or offset their greenhouse-gas emissions by 2050. Around a third of the companies in the S&P 500 index now have such pledges, up from 1% in 2018, a Bank of America study found.

Sales of carbon credits in the voluntary market that includes the CDM reached nearly $2 billion for the first time last year, according to environmental finance data provider Ecosystem Marketplace, and estimates of the market’s size over the next decade range from $50 billion to $180 billion annually, according to the carbon-credit industry trade group Taskforce on Scaling the Voluntary Carbon Markets.

While that is much smaller than the markets that grew out of strict cap-and-trade regimes imposed by governments in Europe and elsewhere to force major polluters to limit their carbon output, the voluntary market plays an outsize role in efforts by a broad cross-section of corporations to position themselves as good environmental stewards.

The CDM represented an early effort to establish a carbon-credit market. What its designers didn’t realize at the time was how quickly renewables would blossom, fed by separate government subsidies that drove huge increases in scale, which in turn lowered prices of components for solar panels and wind turbines. These days, the cost of generating electricity from such sources is roughly on par with that of fossil fuels.

M. Massamba Thioye, a project executive for the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, defended the CDM’s legacy, arguing that it helped accelerate the maturation of the renewable-energy sector, especially in China and India. “In the absence of the CDM, we would not have the same situation,” he said.

Although the original CDM program all but shut down after 2012, its projects continued pumping out millions of credits for years, many of which have recently come on the market.

As the CDM stepped back, two nonprofits established by environmental and business leaders moved in to act as arbiters of what qualifies as a carbon credit, and also to register credits so they can be sold and claimed by only a single party. Gold Standard, started in Geneva, with backing from environmental and climate groups such as the World Wide Fund for Nature; and Verra, based in Washington, D.C., say they are raising standards for the voluntary carbon market, and corporations rely on them to give a seal of approval to their purchases.

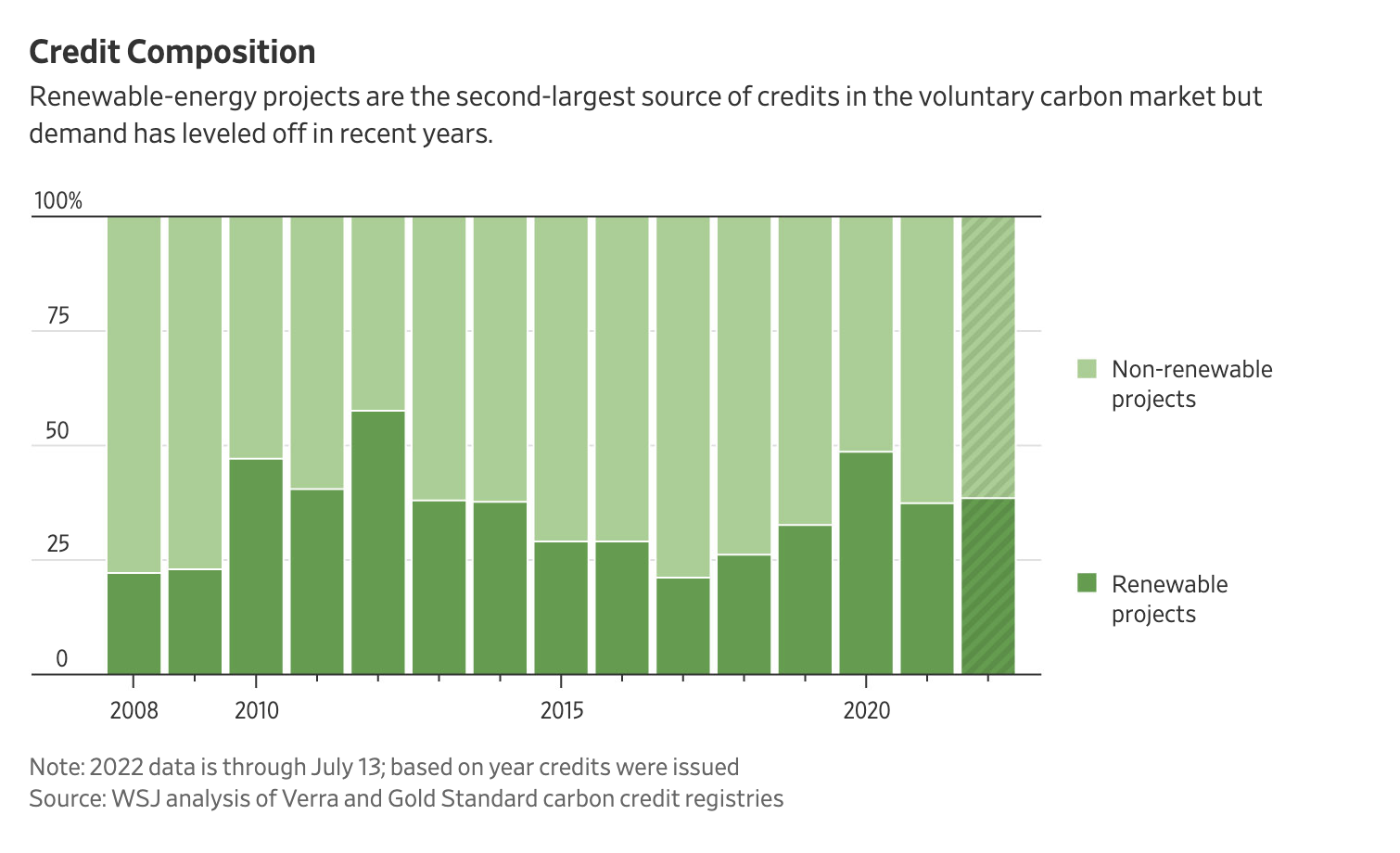

Both Gold Standard and Verra stopped accrediting new renewable-energy projects in 2020, acknowledging that they tend to be profitable on their own. But they decided to grandfather older, CDM-era projects and allow them to issue new credits until roughly 2030, arguing that to do otherwise would have created uncertainty in the marketplace.

Verra’s chief executive, David Antonioli, disputes the idea that old credits siphon away money from more-deserving initiatives. The Verra registry includes numerous new projects such as one that substitutes efficient cook stoves for open-pit fires or others that improve agricultural processes to curb the production of CO2.

Gold Standard’s role is to help the market buy the highest-quality credits, not police it, said the Geneva-based certifier’s chief technical officer, Owen Hewlett.

In the voluntary marketplace, credits linked to CDM-era renewable-energy projects tend to be less expensive, reflecting the perception that they aren’t very effective at reducing greenhouse-gas emissions.

More than a third of the credits bought by companies and others last year—54 million—were generated by such projects, according to a Wall Street Journal analysis of credits verified by Verra and Gold Standard.

Spotify AB, Boeing Co., Lyft Inc., Delta and many others have loaded up on credits that originated under the CDM and were then repackaged through Verra and Gold Standard.

Spotify declined to comment. Lyft will move away from using carbon credits by shifting to all-electric vehicles on its platform by 2030, a company spokesman said. Boeing carefully selects the credits it buys to ensure they cause no net harm, a company spokesman said.

In June, the U.S. Commodity Futures Trading Commission said it was looking at the quality of carbon credits and the growth of the market. “Concerns about transparency, credibility, and greenwashing may hamper the integrity and growth of these markets,” CFTC Commissioner Christy Goldsmith Romero said in a speech.

United Airlines’ Chief Executive Scott Kirby is among critics of voluntary carbon offsets, charging that they allow buyers to tout their emissions reductions while failing to take effective action to limit climate change. He calls these credits “borderline fraud” that allow CEOs to “pretend that they’ve done the right thing for sustainability when they haven’t made one whit of difference in the real world.”

He said United is committed to getting to zero emissions over the longer term by investing in nascent technologies that capture carbon from the air and in companies developing alternatives to jet fuel.

The CDM emerged from the 1997 Kyoto Protocol, which allowed industrialized countries to meet greenhouse-gas reduction goals by funding projects elsewhere.

The program set off building sprees of solar, wind and hydro power projects launched by giant companies and funded by governments. By the end of 2011, the U.N. program had nearly 4,000 registered projects, nearly half of which were wind farms or hydroelectric facilities mostly in China and India, according to an analysis of U.N. data from the Copenhagen Climate Center, a climate-advisory institution.

Chinese wind power capacity eligible to sell credits grew by 70% or more each year between 2006 and 2012 and at one point accounted for 90% of the country’s overall wind energy capacity, the Journal’s analysis shows—meaning that big chunks of the wind industry in China were at least partially funded by Western companies seeking offsets.

But China has struggled to use its wind power, which means in practice the credits did little to offset carbon emissions. Some turbines weren’t connected to the power grid and others couldn’t sell electricity as grid operators rejected wind energy in favor of traditional fossil-fuel sources, according to researchers from Carnegie Mellon University.

Music-streaming service Spotify turned to carbon credits when making an aggressive emissions pledge in 2021 to effectively eliminate its greenhouse-gas emissions in the next decade. The effort “can’t be something we do on the side—it has to be integrated into our everyday business,” the company said.

Spotify emitted 309,400 tons of carbon in 2020, according to its sustainability reports. The company has since bought 202,000 carbon credits identified by the Journal, half of which came from renewable energy projects like the ones that originated under the CDM. One batch of nearly 6,000 credits came from wind farms built by a utility with more than $8 billion in revenue in 2021 that is owned by China Three Gorges Co., the builder of the namesake dam and one of the world’s largest energy firms.

The wind farms are located in Gansu province in North Central China, which rejected a third of the available wind power in 2017, according to a state agency, the same year some of the credits bought by Spotify were generated, according to Gold Standard’s carbon credit registry. By 2020, Gansu was still rejecting 6.4% of the wind energy.

Like other companies, Spotify has bought better-quality credits too. About 18% of the credits bought by Spotify were for typically more expensive forestry credits such as a project to restore land in Panama destroyed by cattle grazing.

In India, wind capacity from subsidized carbon credit projects grew by 25 times between 2006 and 2012, eventually accounting for half the country’s overall wind capacity, according to the Journal’s analysis.

In 2011, Spain’s Acciona applied to the U.N.’s CDM program to create and issue carbon credits from a string of wind farms it was building in India. Construction on the Tuppadahalli wind farm began in 2010 and the next year it was ready to generate electricity, according to Acciona news releases. In 2012, the project was approved by the U.N. to issue credits based on an assumption the clean electricity generated from wind would annually displace an average of 129,000 tons of CO2 by reducing reliance on fossil fuels.

Researchers from Georgetown University, the University of Virginia and the London School of Economics faulted such reasoning. The researchers identified 265 Indian wind-farm projects, including Tuppadahalli, that they said likely should have been denied approval because similar projects were profitable without the sale of carbon credits.

Tuppadahalli didn’t sell any CDM credits in its early years, and in December 2012, the project registered with Verra. Acciona sold only a handful of credits until 2021, when Delta Air Lines stepped up to the plate.

In 2020, Delta announced plans to spend $1 billion on sustainability efforts over the next decade to become the “first carbon neutral airline globally” on investments including more fuel-efficient fleets, technologies to remove carbon dioxide from the atmosphere and carbon credits, according to a news release, company comment and a Journal analysis of registry data.

In April 2021, Delta purchased 13 million credits for $30 million from several projects including one that protects rainforests in Indonesia and from the Tuppadahalli wind farm, according to a press release and a Journal analysis of registry data.

To justify the sale of the credits, Acciona said its wind farm needed the money because rising costs made the project less profitable, according to correspondence between Acciona and an auditor validating the company’s request to issue new credits.

Verra, which very rarely rejects requests to issue new credits when conducting reviews, allowed Acciona to proceed, said the manager of Verra’s Climate, Community & Biodiversity Standards program, Christopher Chapman.

-Phred Dvorak contributed to this article.

Write to Shane Shifflett at Shane.Shifflett@wsj.com

Appeared in the September 9, 2022, print edition as ‘Renewables’ Success Skews Carbon Market’.