Businesses across the country are being hit by delays in a federal program that allows tens of thousands of low-skilled seasonal workers into the U.S. each year, reigniting a clash over the program’s merits and whether it harms domestic workers.

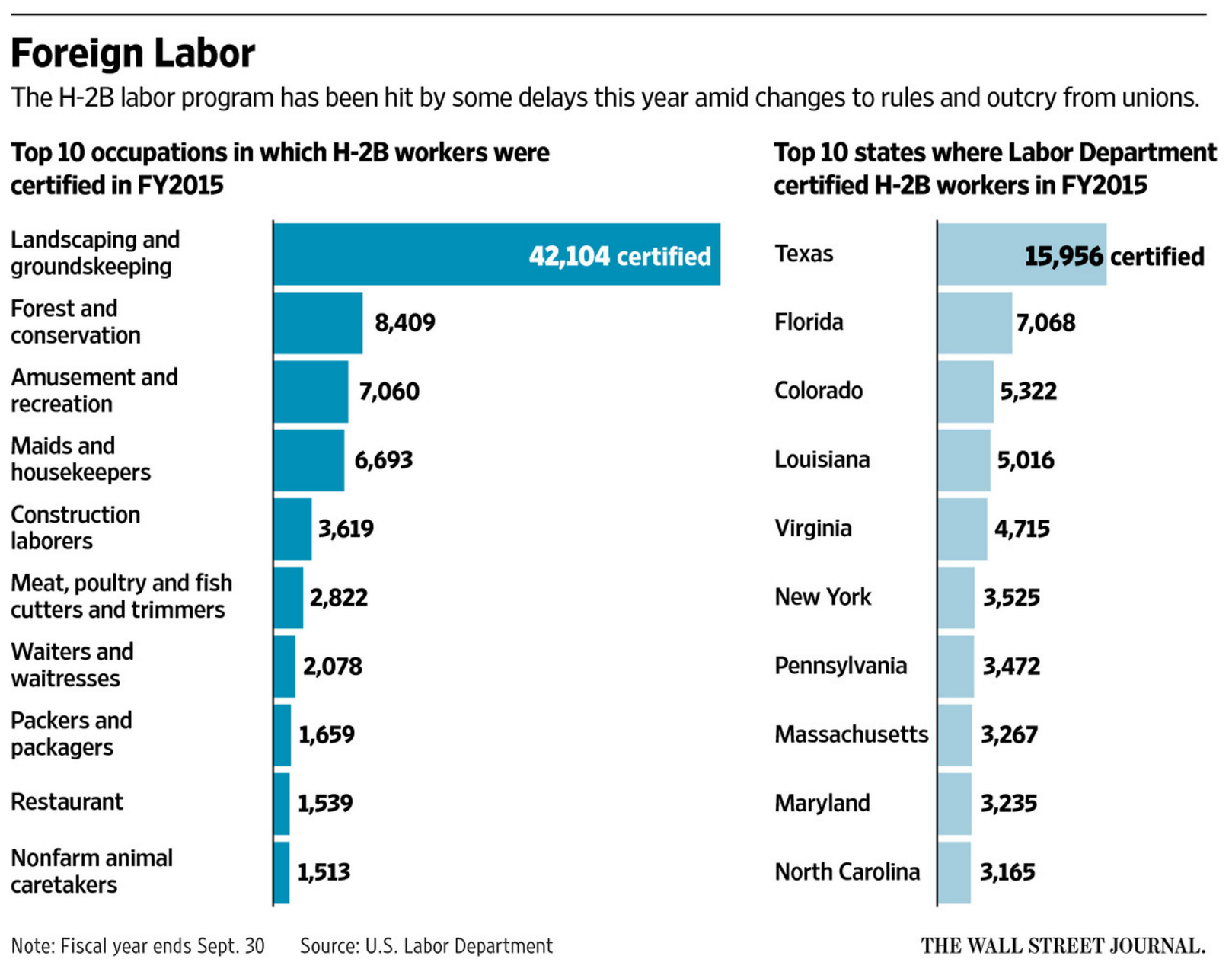

Companies say the small H-2B visa program—used mostly in the landscaping, forestry, amusement, tourism and construction industries—is a key conduit for seasonal staff to do jobs they say Americans typically don’t want.

Russ Kissel’s amusement-ride company, Kissel Entertainment, got caught in the slowdown this month when he and his wife failed to get approval in time for 75 carnival workers to operate a fair in Alabama. The Okeana, Ohio, company canceled the fair and lost as much as $50,000 in expected revenue.

“I’ve got to figure out a way to limp by until they do get here,” said Mr. Kissel, who will keep the workers until November if they arrive.

Unions and their allies say the program cheats Americans out of jobs and subjects guest workers to inadequate wages and working and living conditions, driving down wages for U.S. workers. The program, which caps the annual number of visas at 66,000 but could swell this year under a recent spending-bill provision in Congress, is distinct from the somewhat larger H-2A program, which brings in seasonal farmworkers.

Seeking to address some of these issues, the Department of Labor and Department of Homeland Security implemented new H-2B regulations in April. They expanded the recruitment employers must undertake to find U.S. workers and required that guest workers be paid the region’s prevailing wage for that kind of work.

Unions and others call it a good step but want more changes. “The H-2B program is being used in industries where there’s high unemployment,” said Joleen Rivera, an AFL-CIO legislative representative. “If employers were offering more-attractive wages, they would be able to find American workers.”

Vermont Sen. Bernie Sanders has criticized the program as part of his bid for the Democratic presidential nomination, recently citing a report that likened guest-worker programs to slave labor—a comparison that angered employers.

In recent weeks the Labor Department—which has to certify employers’ H-2B applications before the process can advance to the Department of Homeland Security—has been experiencing processing delays, it said in a January statement.

After more outcry over those delays from lawmakers and their business constituents, the Labor Department on Friday announced an emergency processing plan to alleviate the backlog. It said in that statement that the delays are “significant” and “impair the ability of employers to hire foreign workers when needed.” It’s unclear how fast, or how much, it will fix things.

The business community suspects the Labor Department has been slow-walking the process to appease unions and other critics, many of whom are traditional Democratic allies. The agency blames technical problems in its electronic filing system and a twofold increase in applications from late December through mid-January from the year-earlier period.

The surge followed the December passage of a one-year congressional spending bill that effectively increases the number of H-2B guest workers allowed this year. It will do that by permitting returning workers from the past three years to not count toward the 66,000 visa cap. The Congressional Budget Office has estimated the change will increase the number of H-2B workers by about 8,000 in fiscal-year 2016 and said it was unlikely that the number of additional workers would reach the theoretical maximum of 198,000, which is three times 66,000. Many employers say a number of the foreign guest workers they use return to them year after year.

The bill made other changes, and implementing all revisions caused a 17-day “processing pause” at a national Labor Department processing center in Chicago, the agency said, though the business community remains skeptical.

“The Department of Labor, either through incompetence or by design, is making it very difficult for our members to hire seasonal workers,” said Kristen Fefes, executive director of the Associated Landscape Contractors of Colorado, one of dozens of groups speaking out on their members’ behalf.

Ms. Fefes said most landscape employers in Colorado—a state whose number of H-2B workers trails only Texas and Florida—need their workers by the beginning of April. If the backlogs aren’t addressed immediately, it could stall millions of dollars in landscape work, she said.

Antoine Williams, office manager for Environmental Designs Inc., a landscaping business in Henderson, Colo., said the company awaits 116 Mexican guest workers it needs by April. Without them, the company could lose $500,000 or more in business and be forced into layoffs, he said. “It just seems like all of a sudden this has become a huge issue.”

Even a small absence of workers can make a big dent. Jake’s Seafood Restaurant in the coastal town of Wells, Maine, needs eight Jamaican cooks for the summer tourism season. But it hasn’t received a green light from the Labor Department to advance its application, which could take two more months to complete.

Without the workers, the restaurant will be open five days weekly instead of seven and won’t hire as many dining-room staff, said owner Jake Wolterbeek. He estimates that this and earlier closing times would shave at least $60,000 from the roughly $200,000 in monthly revenue he expects in July and August.

“Why do we have to call our senators and representatives and beg for help,” he said.

In a list of written answers that the Labor Department provided The Wall Street Journal on Thursday night, it denied deliberately slowing its processing and said the business community supported the congressional changes that contributed to delays.

The agency said it has expanded and reallocated resources to help. Still, the emergency processing won’t resolve the entire backlog problem, it said. Labor Secretary Thomas Perez wants “comprehensive immigration reform” that updates temporary guest-worker programs “as part of a long-term fix to a severely broken system,” the agency said.

This article was originally published by the Wall Street Journal and written by Melanie Trottman. Write to Melanie at melanie.trottman@wsj.com. View the full article at wsj.com.