Hundreds of companies plan to achieve their climate goals using carbon credits to offset the emissions they can’t eliminate on their own. Soon there might not be enough of the credits to go around.

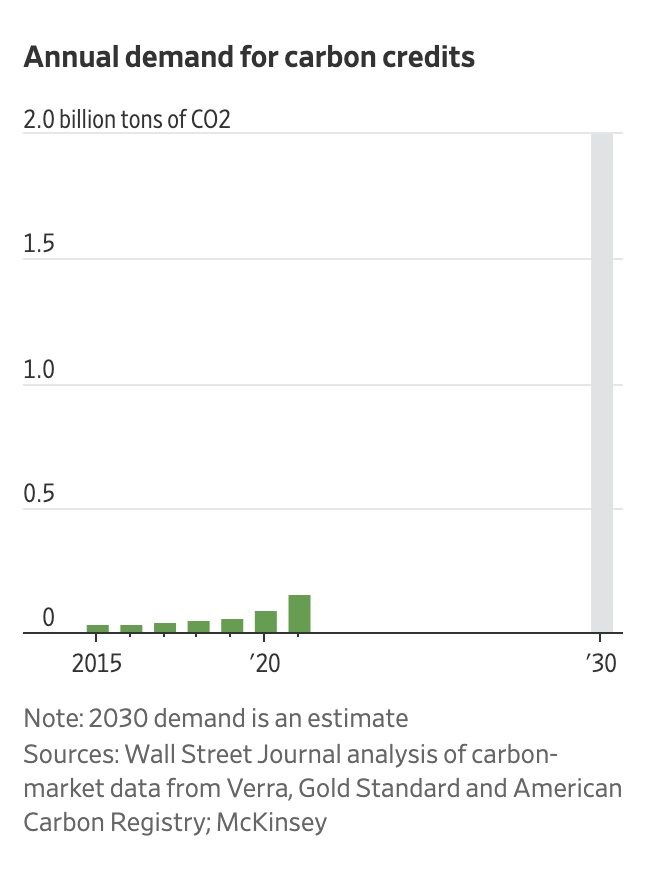

Despite record demand for carbon credits last year, supply of new offsets has still outpaced demand. That has created a surplus that has has kept most carbon credits cheap.

The surplus could soon turn to shortage as businesses, acting to meet their climate pledges, boost demand. That will make it harder and more expensive for companies to claim to be offsetting their emissions. Demand for carbon credits could also run up against other important uses for land, such as farming.

Carbon credits are typically issued by projects that preserve forests, which absorb greenhouse gases, or by renewable energy projects that replace fossil fuels. Each credit represents the reduction or removal of one ton of carbon dioxide from the atmosphere. These credits are part of the so-called voluntary carbon markets. There are mandatory markets in places such as Europe and California that operate differently.

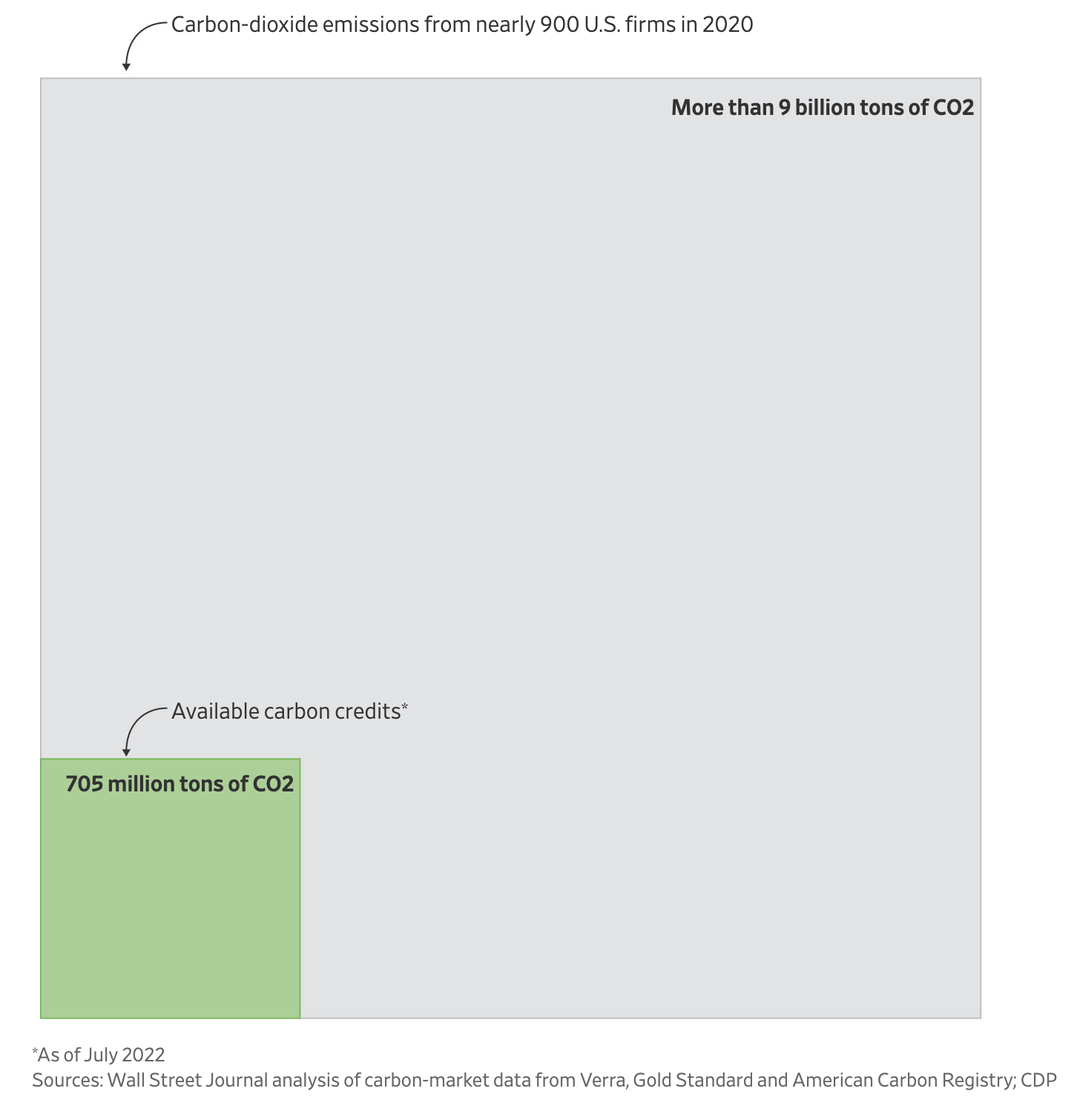

A record 156 million carbon credits were purchased by companies, governments and individuals last year, according to a Wall Street Journal analysis of carbon-market data. The current surplus is 705 million credits, according to the Journal’s analysis.

Those credits cover a fraction of the carbon-dioxide emissions produced by U.S. businesses. In 2020, nearly 900 U.S. companies produced more than 9 billion tons of carbon dioxide, according to CDP, a not-for-profit that surveys businesses’ environmental goals.

Available carbon credits compared with carbon-dioxide emissions in 2020

Not all of those 9 billion tons of carbon-dioxide emissions will be offset using carbon credits. Some will likely continue for decades and some will be reduced by efforts such as boosting efficiency and switching to renewable energy.

More than 600 of those 900 U.S. companies have targets to shrink their carbon footprints over the next three decades or less, according to CDP’s data. Of those, the Journal identified more than 70 companies that have used carbon credits in the past. That group, which is full of big emitters, produced nearly 2.4 billion tons of carbon dioxide in 2020.

If those companies tried to offset all of their emissions with carbon credits, they would wipe out the surplus of credits built up over years in roughly four months.

Projections for credit demand keep rising. Consulting firm McKinsey & Co. predicts that annual demand for carbon credits could reach more than two billion within the next decade based on company statements, climate industry experts and net-zero goals.

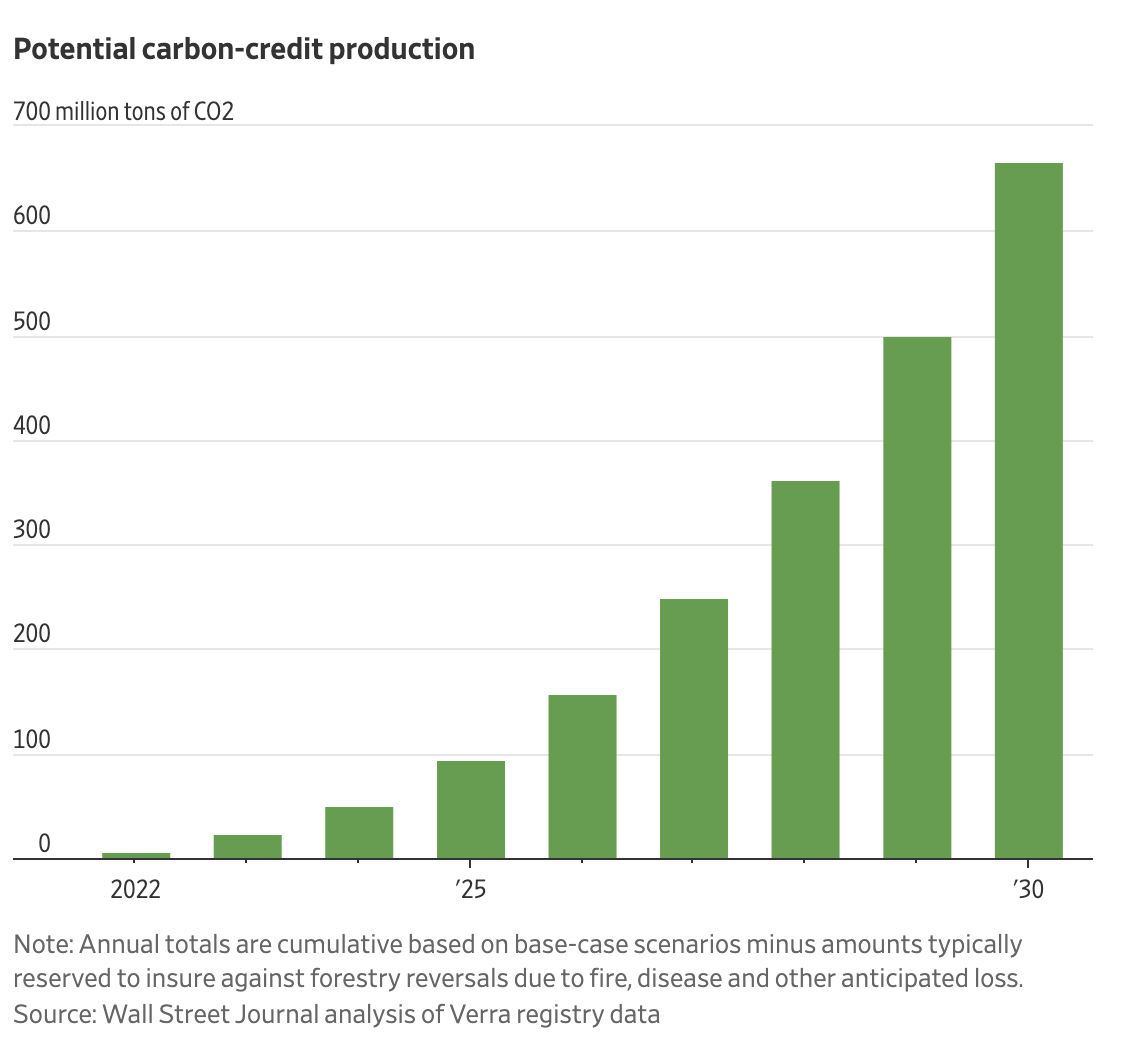

The two primary types of credits—renewable energy and forest preservation, which together account for the bulk of credits—have limits to their growth. The risk is that rising demand leads developers to produce credits that do little to reduce carbon emissions. This has already been a problem in the market.

A key requirement of the credits is that the funding they provide is necessary for the projects to get done. As costs for renewable energy have fallen, projects that don’t need funding still qualify to issue credits, Journal reporting shows. That allows developers to profit from the sale of power and of credits, undercutting the basic requirement for their issuance.

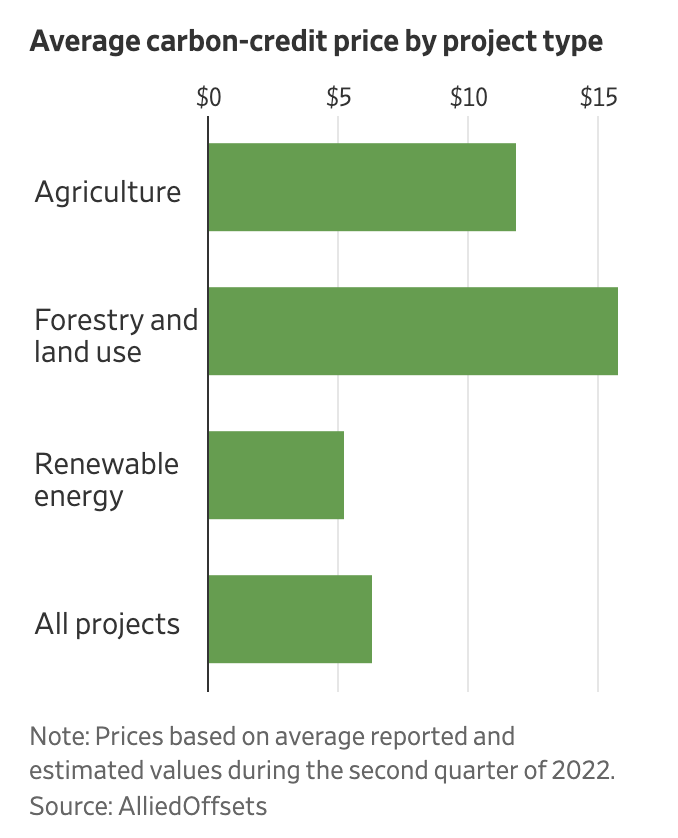

Credits from projects that prevent deforestation or plant trees along with other agricultural and land-based carbon-mitigation practices make up nearly 50% of the available supply, according to the Journal’s analysis of the University of California Berkeley’s carbon-credit database. These projects are costly and complicated. They often require preserving or developing vast tracts of land and protecting them for an average 30 to 70 years to absorb enough carbon dioxide to generate a steady supply of credits.

One risk is forest fires, which can wipe out the trees that were supposed to hold carbon. Another is the demand for land, which can run up against other uses such as agriculture, according to a recent study by National University of Singapore’s Centre for Nature-based Climate Solutions.

“The money you can get from cropland products is more lucrative than planting trees,” said Qiming Zheng, the study’s lead author. To compete with agriculture, carbon-credit prices need to reach about $40, Mr. Zheng said. Last quarter, the estimated value of purchased carbon credits averaged $6.33, according to Allied Offsets.

Earlier this year, forestry startup NCX raised $50 million to expand its program paying timber farmers to defer harvests and sell credits based on the amount of carbon absorbed by the still-standing trees. In June, farming startup Indigo Agriculture issued its first batch of credits after raising more than $1 billion to pay farmers to implement carbon-saving practices on their lands.

Companies are investing to cover their own demand. In July oil producer and trader Shell PLC invested $40 million for a minority equity stake in a Brazilian carbon-credit developer focused on forestry projects, the company recently announced.

Shell plans to spend about $456 million on nature-based projects that protect or restore forests, grasslands and wetlands in the coming years and aims to offset 120 million tons of carbon annually by 2030, according to the firm’s recent sustainability report. That is a fraction of the 675.6 million tons of carbon dioxide the company emitted in the 12 months that ended May 31, according to MSCI.

That means Shell faces a choice between producing less fossil fuel and buying far more offsets than it had planned. Shell, the second-biggest buyer of offsets identified by the Journal, says it will wean itself off offsets.

“Our future requirements for offsets largely depend on the speed with which customers move to using zero- and lower-carbon energy,” said Shell spokeswoman Anna Arata.

Write to Shane Shifflett at shane.shifflett@dowjones.com