No one knows for sure why some pine boards are weaker today than they were a decade ago, but it seems modern growing techniques – genetic selection, fertilizing and thinning for maximum growth – aren’t the problem.

In 2013, the Southern Pine Inspection Bureau downgraded the standards for visually inspected pine board, basically finding that the wood couldn’t support the same load it had in the past, forcing builders to alter plans to compensate for weaker wood. The SPIB sampled pine from across the South and found it weaker, but couldn’t say why.

The controversial change in standards sent forestry folks into a whirlwind of speculation. Was modern silviculture producing lower quality wood?

Results of a recent study by the University of Georgia in partnership with Plum Creek show that timber producers can use intensive growing methods and come out with lumber just as strong.

“We were trying to see, if we grow trees as we intend to, are they as strong? Are cultural practices impacting board strength?” said Dale Hogg, a forester with timberland company Plum Creek.

“It was important for us to understand and to be able to educate people,” Hogg said. “It cemented what we already believed to be true.”

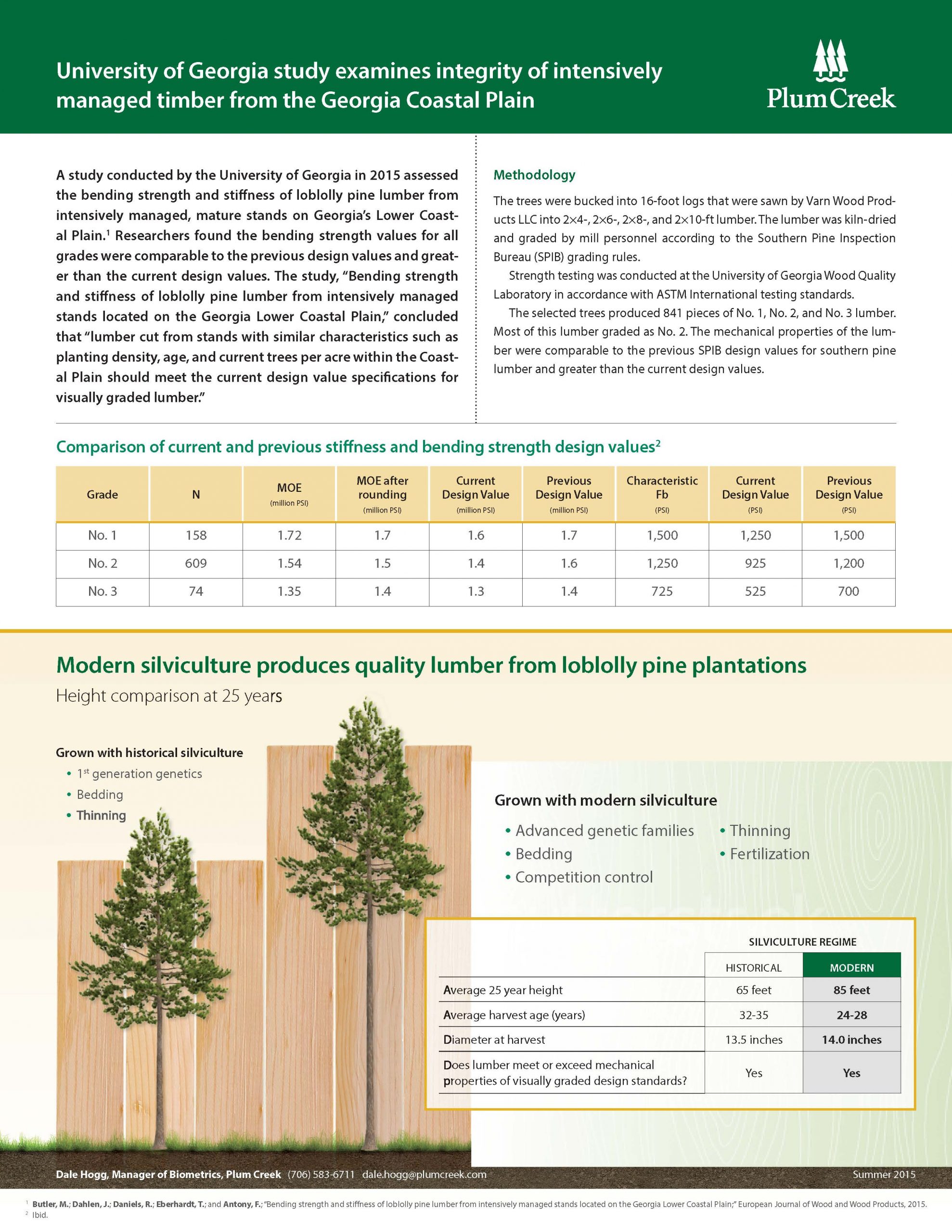

Earlier this year, UGA foresters tested the bending strength and stiffness of loblolly pine lumber from intensively managed, mature tree plantations on Georgia’s Lower Coastal Plain.

Here’s what they did:

Trees were harvest from intensively managed Plum Creek loblolly pine plantations in Georgia’s Coastal Plain. The trees were bucked into 16-foot logs that were sawed into 2×4-, 2×6-, 2×8-, and 2×10-ft lumber. The lumber was kiln-dried and graded by mill personnel according to the SPIB grading rules.

The University of Georgia Wood Quality Laboratory then tested how much force it took to break the boards.

Researchers found the lumber was comparable to earlier design standards for Southern pine lumber and stronger than the design values put into place in 2013.

The study, “Bending strength and stiffness of loblolly pine lumber from intensively managed stands located on the Georgia Lower Coastal Plain,” concluded that “lumber cut from stands with similar characteristics such as planting density, age, and current trees per acre within the Coastal Plain should meet the current design value specifications for visually graded lumber.”

This means that foresters and landowners using advanced forestry techniques to grow trees faster, have not affected the quality (strength and flexibility) of the boards produced from loblolly plantations.

For the project, foresters picked intensively managed trees. If modern silviculture was causing weaker board, these trees would be the first to show the difference.

“They were essentially the fastest growing trees in (Plum Creek’s) inventory that were already 25 years old,” said Joe Dahlen, the lead researcher on the project for UGA. Click here to see the diagram that compares the average heights and mechanical properties of loblolly pine trees grown with and without the advantages of modern silviculture.

While timber experts want to understand why the samples tested by SPIB were weaker, they don’t quibble with the findings.

One popular theory attributes the reduced lumber strength to younger trees. With less demand for lumber during a housing downturn, owners of mature stands had more incentive to hold onto the investment rather than cut while prices were low. Those economics pushed more small-diameter trees into the stock, the theory goes.

Since most tests happen after milling, it’s difficult to validate or disprove the theory.

The UGA research is getting closer, though.

“We took a different route and took a lot of data about where the trees were growing,” Dahlen said.

Now, he would like to expand the research to many more locations, using non-destructive methods to test the density of trees.

But the board-snapping work likely will continue, too, as researchers try to determine how to grow strong trees in a relatively short period of time.

“We built a lab to do this, so we’d like to use it,” Dahlen said.